Find The Others

On Technoscepticism, Digital Alienation, and The Net

On Technoscepticism, Digital Alienation, and The Net

The morning after, I confidently told my partner that, for the sake of my mental well-being, I’d be avoiding American politics for the foreseeable. With an inevitability that would make a multi-cam sitcom writer blush, I proceeded to spend the rest of the morning listening to post-election autopsies.

Later, a friend texted “Fancy a lunchtime What The Fuck walk?” I did. We wandered around the park as we found various ways to say “What The Fuck” and bought doughnuts. That evening, a group of us went to a pub quiz. We drank, ate tacos, and tried to remember the name of that Little Mix song.

It was nice to be with other people. It was nice to not be scrolling.

We came third.

“It's like I'm not even me anymore.” - Angela Bennett

Irwin Winkler’s proto-cyber thriller, The Net, was released almost 30 years ago, in 1995 - commonly regarded as the year that Hollywood discovered the internet. Sandra Bullock played social recluse and computer-nerd-for-hire Angela Bennett. She uncovers a sinister plot by a computer security firm and finds her life turned upside-down as they attempt to destroy the damning evidence, and her credibility. Her job, house, money and her entire identity are seemingly deleted with some judicial tweaks to key computer records.

Bennett is uniquely - conveniently - well positioned for this identity annihilation. Her mum, in the throes of dementia, doesn’t recognise her; she works from home; her social circle is limited to an online chat room; she orders takeaways from pizza.net; her neighbours don’t even know what she looks like. An isolated loner. Her most reliable companion: the screen in front of her. A wild, unimaginable scenario that I’m sure none of us can relate to.

“Just think about it. Our whole world is sitting there on a computer. It's in the computer, everything: your DMV records, your social security, your credit cards, your medical records. It's all right there. Everyone is stored in there. It's like this little electronic shadow on each and every one of us, just begging for someone to screw with, and you know what? They've done it to me, and you know what? They're gonna do it to you.” - Angela Bennett

While the big bad of The Net is a sort of evil Norton AntiVirus software company, its preoccupying fear is more fundamental: If all of our data is digitised - what if someone tampers with it? If we spend more of our lives on the computer, who will have access to that information?

This period of Hollywood’s flirtation with the internet is often referred to as the era of the technophobic thriller, but that’s a surface-level misreading. Technosceptic might be more accurate. These films were broadly positive and excited about new technology. Often treating it like the new rock ‘n’ roll. Tech almost always played a role in saving the day. Rather, these films were more concerned with who had ultimate control of these tools, and whether or not we needed to place restrictions on them.

“Any of these technologies could be steered toward extending our human capabilities and collective power. Instead, they are deployed in concert with the demands of a marketplace, political sphere, and power structure that depend on human isolation and predictability in order to operate.” - Douglas Rushkoff (Team Human)

Watching it in 2024, however, the most prescient part of The Net is Angela Bennett’s digital alienation.

What was originally a series of Possible Enough contrivances to make Bennett’s identity theft more believable, are now just part of our everyday lives. We can all bank, shop, eat, work, and socialise without seeing another human being face to face. Furthermore, we’ve all been through covid lockdowns where it was actively encouraged to socially distance. Personally speaking (while acknowledging we’re obviously not in a post-Covid world), it has taken me a couple of years to shake a more pronounced awkwardness in social situations and I still feel a step or two behind where I once was.

“They knew everything about me. They knew what I ate, they knew what I drank, they knew what movies that I watch, they knew where I was from, they knew what cigarettes I used to smoke, and everything they did, they must have watched on the Internet, I don't know, watched my credit cards? Our whole lives are on the computer, and they knew that I could be vanished. They knew that nobody would care, that nobody would understand.” - Angela Bennett

Angela Bennett is not alone in feeling like this. In 2023, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared loneliness to be a pressing global health threat. According to their International commission, the WHO estimates that 1 in 4 older adults experience social isolation and between 5 and 15% of adolescents experience loneliness. In the US, social isolation is a greater public health problem than obesity.

“People lacking social connection face a higher risk of early death. Social isolation and loneliness are also linked to anxiety, depression, suicide, and dementia and can increase risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke.” - World Health Organisation

Meanwhile, recent studies suggest we’re spending, on average, just under 7 hours a day looking at screens.

How much these things are related is an ongoing debate, but I think it’s fair to say:

1. People are increasingly feeling alienated and alone.

2. We’re all spending more time on our phones and computers.

In this sense, Angela Bennett is all of us in 2024. We are all Angela Bennett.

As Bennett’s digital alienation makes her more vulnerable to pernicious actors who wish to remove her agency, so too are we increasingly at risk from those who don’t have, and have never had, our best interests at heart.

“Without socially positive opportunities to exercise our autonomy, we tend toward self-promotion over self-sacrifice and fixate on personal gain over collective prosperity. When we can’t see ourselves as part of an enduring organism, we focus instead on our individual mortality. We engage in futile gestures of permanence, from acquiring wealth to controlling other people. We respond to collective challenges such as climate change through the self-preservation fantasy of a doomsday prepper.” - Douglas Rushkoff (Team Human)

“We have sealed ourselves away behind our money, growing inward, generating a seamless universe of self.” - William Gibson (Neuromancer)

This is all, ultimately, just an extension of the “there’s no such thing as society” neoliberal individualism as established by Margaret Thatcher and the economist Friedrich Hayek.

As such, to blame Silicon Valley for our modern day social isolation would be overly simplistic. In Multitudes: How Crowds Made the Modern World, Dan Hancox examines the ways in which crowds have been demonised and othered by those in power (see: the commonplace usage of the word “mob” when talking about a large group of people). He suggests our alienation is much more structural:

“Whether through government cuts or concessions to the expansive ambitions of private enterprise, a key reason we have all become a bit more crowd-shy in recent decades is the prolonged, top-down assault on public space and the wider public realm – what are sometimes called the urban commons. From properly funded libraries to pleasant, open parks and squares, free or affordable sports and leisure facilities, safe, accessible and cheap public transport, comfortable street furniture and free public toilets, and a vibrant, varied, uncommodified social and cultural life – all the best things about city life fall under the heading of the public realm, and all of them facilitate and support happy crowds rather than sad, alienated, stay-at-home loners.” - Dan Hancox (Multitudes)

States have largely outsourced our social connectivity to tech companies whose business models are not built around the public good, but rather engagement. The attention economy is paramount, The Algo our new, capricious God. Now, even the people/artists/friends we ostensibly “follow” are withheld from our feeds based on the whims of whatever fickle CEO is in charge of your favoured social media network. If your livelihood depends on engagement on these things, the temptation is to stop thinking about human connection and to think more about what will satisfy The Algo to ensure a good harvest.

I’m lucky. I live with my partner. I have friends who suggest spontaneous and vital What The Fuck walks. But I work from home and spend most of the day largely not talking to anyone. I’m not immune to feeling isolated, anxious and hopeless as I stare unblinking at my news feed. I think we all feel it. It’s easy to feel unconnected with society. Powerless. Alone. We are all Angela Bennett.

Weaponising that alienation, as the antagonists of The Net do against Bennett, can of course be used for exploitative purposes like identity theft. But it can also have much more nefarious applications: Our loneliness can be manipulated to make us consume more, to work longer, to turn us against ourselves, and each other.

I think this is a useful way to understand what is happening as fascism takes root globally:

“Totalitarian movements are mass organisations of atomised, isolated individuals [...] Such loyalty can be expected only from the completely isolated human being who, without any other social ties to family, friends, comrades, or even mere acquaintances, derives his sense of having a place in the world only from his belonging to a movement, his membership in the party.” - Hannah Arendt (The Origins of Totalitarianism)

But as Rushkoff urgently points out, it doesn’t have to be this way:

“We live with a bounty of communications technologies at our disposal. Our culture is composed more of mediated experiences than of directly lived ones. Yet we are also more alone and atomized than ever before. Our most advanced technologies are not enhancing our connectivity, but thwarting it. Sadly, this has been by design. But that’s also why it can be reversed” - Douglas Rushkoff (Team Human)

We can delete the most toxic social media accounts, practise healthier screen routines, limit our exposure to doomscrolling… But we can also organise collectively; join a union; join a local club; ask our friends if they need a What The Fuck walk; write about it all in relation to a largely forgotten Sandra Bullock thriller from the 90s. That sense of hopelessness and alienation is what the powerful want us to feel.

“It is rational for those in power to continue to demonise and pathologise crowds, because crowd membership offers us a level of freedom and strength we can never achieve alone. It amplifies the very best in us, empowers us, and makes us happier, more secure people.” - Dan Hancox (Multitudes)

Is it a reach to see all of this in 1995’s The Net? Maybe. Let’s be clear: this is a film that requires Sandra Bullock to explain what IRL means to an empty room. There’s a quaint nostalgia to the janky 90s tech and UX design, but it’s an aggressively mediocre film (that said, it was one of Carl Reiner’s favourite films ever apparently).

Winkler, better known for his producing role for films like Goodfellas and Rocky, brings a fairly traditional paranoid thriller directorial approach that is sub-Alan J. Pakula at best. The crash zooms into words on the screen like “Mainframe” are unintentionally hilarious. To paraphrase Logan Roy: I love it, but it is a deeply unserious film.

The film works because of Sandra Bullock. Her inherent charm and vulnerability on screen is perfectly suited for a leading role in a conspiracy thriller like this. According to one of the consultants on the film, she was ahead of the curve when it came to computer acting too:

“She could act with the computer. That sounds simple because it's secondhand for everybody now, but back then, some people could say lines or they could click mice, but they couldn't do them at the same time, and that was always super awkward. Sandy was just a natural.” - Alex Mann

The Net was uniquely placed at a point where the Internet Superhighway was only faintly being understood as the New Frontier. Before the dotcom boom and bust, before Web 2.0, before the walled gardens and the Dead Internet Theory. In that sense it remains a fascinating time capsule of a moment when the possibilities of what was to come felt endless.

Of the raft of 1995 technothrillers (Hackers, Strange Days, Virtuosity, and Johnny Mnemonic), The Net did the best at the box office despite unenthusiastic reviews. But not well enough to usher in an era of Cyber Cinema. Hollywood gave the technothriller another shot with 2001’s Antitrust (Dir. Peter Howitt) in which Ryan Philippe finds himself caught in a Silicon Valley conspiracy led by a crisp-munching Bill Gates/Steve Jobs composite played by Tim Robbins. It didn’t make its budget back.

It took David Fincher, famous for his dark serial killer thrillers, to inherently understand that these films should be shot like dark serial killer thrillers. In his 2010 masterpiece, The Social Network (that trailer might be a masterpiece too), Fincher lights and frames Mark Zuckerberg like a psychopathic killer stalking his prey. The blue glow of the computer is both a soothing balm and something approaching a possessing force. Thus, what could have been a brightly lit, Capitalism Yay! biopic instead finds itself part of the 90s technosceptic thriller lineage.

The Net’s most obvious successor is Steven Soderbergh’s criminally overlooked Covid-adjacent 2022 thriller, Kimi. In it, Zoë Kravitz plays agoraphobic data analyst Angela Childs who hears a violent attack on a sound recording from an Alexa style device called Kimi. Equal parts The Net, The Conversation, and Rear Window, Kimi is an efficient, tense potboiler that delivers on the promise of the technosceptic 90s. I wish there were more like it.

We can also see The Net’s influence in modern screenlife films like Searching, Host, Unfriended and The Den. But perhaps - hopefully - The Net’s most enduring legacy will be inviting us to go outside, touch grass, talk to another human being, and organise…

“One of the greatest mistakes we have made in recent decades is to accept the idea that freedom is a quality that can be found and enjoyed only by the individual acting alone. Freedom lies within the crowd; it is our obligation to dive in and find it – together.” - Dan Hancox (Multitudes)

“Find the others.” - Douglas Rushkoff (Team Human)

Do You Want to Know More?

- A great oral history of Pizza.net and The Net with insights from the original writers, producers and consultants.

- The Internet Archive has an emulator of the original interactive press pack for The Net which is a lot of fun.

- I’ve used a lot of quotes from Douglas Rushkoff’s Team Human here. It’s a great read. A rallying cry for us to reject our Techno Capitalist Realism and work towards something better.

- I’ve also referenced Dan Hancox’s Multitudes a bunch. Another essential read. Hancox has his own substack - Honor Oak Riot - which I’d also highly recommend.

- The US Surgeon General’s advisory report on loneliness.

- I linked to it in the essay above, but this interview with George Monbiot about the impact of neoliberalism on our collective mental health is excellent.

Bits + Bytes

I hope the prospect of discussing technothrillers from the 90s is up your street as this is Part 1 (of 4) of a planned series!

I’ll be tabling at ECAF next weekend. Saturday 23rd November. 10am until 4pm. Out of the Blue Drill Hall, Edinburgh, EH6 8RG. Come say hi if you’re in town and fancy picking up any of my work!

I’ll also be tabling at TAGS on Saturday 7th December at the Fruitmarket in Edinburgh. 10am until 5pm.

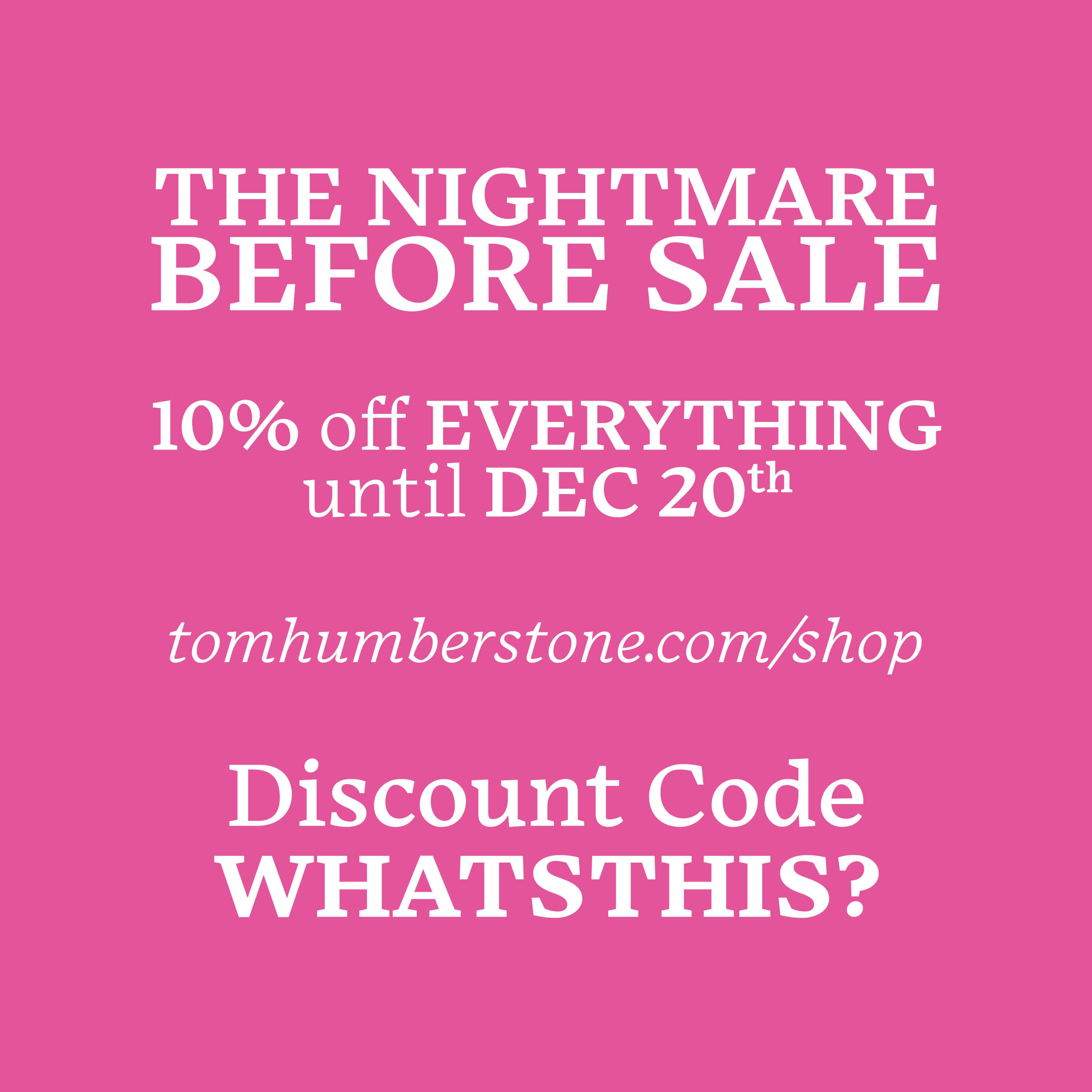

If you can’t make it to either but you’d like to buy my comics/zines/prints as Christmas gifts, I’ve updated my online store to have new, cheaper shipping options. You can also use the discount code WHATSTHIS? for 10% off any order until December 20th. Get orders in early as it gets harder to guarantee arrival before Christmas when we get deep into December.